Banking turmoil, liquidity vacuum, stress tests and margin calls…

« (…) it is frankly amazing to realise that the circumstances that led to this mayhem (very high inflation, inverted yield curve, sharply higher interest rates) do not figure in any of the stress tests performed on either side of the Atlantic. Regulators were unable to imagine this crisis could have happened. (…) The Fed this week expanded its balance sheet by $297bn, taking the overall the balance sheet size back to the same level as last November, and so reversing the efforts of QT. During the 2020 coronavirus-triggered “Dash-for-Cash” it is estimated that combined margin demands increased globally by up to $500bn. For fixed income markets the last week exceeded the shock of 2020 by some margin. It seems the scale of balance sheet expansion places the last week on a par with the March 2020 COVID shock.

(…) The shocking moves in fixed income markets mean clearing houses will remain wary of market volatility. In fact, clearing houses are preparing to impose more margin penalties. The DTCC’s subsidiary, National Securities Clearing Corporation (NSCC) announced on Tuesday that from the end of March it will be able to call for extra margin intra-day for volatility in addition to intra-day calls for mark-to-market changes.«

Source: ExorbitantPrivilege

Despite reassurances, there are several reasons to worry about the health of Europe’s banks, among them, their low profitability relative to their cost of capital

According to the FT, « eurozone banks are still not earning enough profit to cover their cost of capital, which is around 9 per cent for many of them, meaning they are effectively destroying shareholder value… «

It does not look like such inequality is financially sustainable in the long run for any profit seeking private branch of the economy… I wonder whether such pattern can be also be ‘observed’ in other meaningful sectors of the EU economy.

An ECB paper from 2021 on the issue points out that Banks’ cost of equity has been consistently higher than banks’ return on equity since the onset of the global financial crisis.

Price stability versus financial stability

Along the lines of what Christine Lagarde hinted in the European Parliament on Monday 20 March, Willem Buiter sketches what seems to me be the new emerging mainstream consensus as regards an operative path for reconciling price stability with financial stability:

“(…) tension between the objectives of central banks – price stability and financial stability – is inevitable. In such cases, I believe that financial stability must come first, because it is a precondition for the effective pursuit of price stability.

But this does not mean that the central bank should cease or suspend its anti-inflationary policies when threatened with a banking crisis or similar systemic stability risk. The conflict between the objectives of price stability and financial stability should be manageable by using the central bank’s policy rate to target inflation, and by using the size and composition of its balance sheet as a macroprudential policy tool to target financial stability”.

Buiter claims that a template for that was achieved by ECB with the announcement of the Transmission Protection Instrument, then by the BoE during the pension fund turmoil by reversing QT while keeping the pace of interest rate increases and now by the Fed with the Bank Term Funding Program offering one-year loans to banks with the collateral valued at par, (including commercial mortgage-backed securities).

He acknowledges, however, that what the Fed does is ultimately to assume a ‘lender of first resort’ mission:

“With market value well below par for many eligible debt instruments, the lender of last resort has become the lender of first resort – offering materially subsidized loans. The same anomaly (valuing collateral at par) now applies to loans at the discount window.”

Although ultimately Buiter recognizes that that financial stability would require additional reforms of the banking sector, alongside many commentators Buiter is optimistic that the measures adopted by central banks and the tacit guarantee of all deposits will avoid further escalation. Remains for me the question mark of the above-mentioned severe liquidity stress that even if calmed by central banks’ massive interventions is still around. Liquidity lines provided by central banks come with a price… Interest rates along the yield curve are now higher than the returns of a big part of the assets held by the same banks, so the remedies provided to the liquidity vacuum are not painless or at least seem more costly than in the past.

There is also evidence that many investors are withdrawing (some of) their deposits not out of panic but rather because money market funds offer much better returns. According to the FT: « More than $286bn has flooded into money market funds so far this month, (…) The surge this month has helped push overall assets in money funds to a record $5.1tn. » There is breakdown of the inflows here: https://on.ft.com/3Zc0Kni

Therefore, despite central banks interventions, the whole liquidity squeeze with all its consequences may continue. As mentioned by ExorbitantPrivilege:

« With an inverted yield curve, any securities held by banks (both Available-for-Sale and Hold-to-Maturity) will be subject to negative Net Interest Income, which feeds directly through to the bottom line. Banks have tried to compensate for this by keeping interest on deposits low. But surely that game is up (…). Banks can also increase rates payable on loans. Both routes are a monetary tightening(…) »

In the same vein, FT Unhedged, summarizing the findings of a March 2023 Stanford University paper on Mark-to-Market Losses and Uninsured Depositor Runs as follows

(…) there are $2.2tn in mark-to-market losses out there, and there is only $2.2tn in equity in the US banking system (…) Those $2.2tn in mark-to-market losses represent a huge block of assets that are yielding less than market rates, which will create a big and potentially long-lasting drag on bank profitability (…) To use a somewhat morbid metaphor, the heart attack phase of the banking crisis may be over, as the threat of runs subsides in the face of official support for banks. Now, however, we have to see if any banks are going to die slowly, killed by the cancer of declining profit.

It would be interesting to find a similar assessment of unrealized losses in the EU banking system…

Rules for winding up big banks do not work, Swiss finance minister warns:

« In an interview with Swiss newspaper NZZ on Saturday, Karin Keller-Sutter — who was at the centre of Swiss authorities’ rush to rescue Credit Suisse — said that following the emergency protocols that are at the centre of the regulatory architecture for big banks “would have triggered an international financial crisis”.

Even if statements from EU policymakers all over the board have been emphasizing that the EU banking sector is way more robust than in 2008 and that all indicators are ‘technically’ accurate, if Ms Keller-Sutter is right, such declarations do not look particularly reassuring. The Eurointelligence newsletter of Monday 27 March has summarizes the point as follows:

In the Zhuangzhi, an important work of ancient Chinese philosophy, the philosopher Zhuang Zhou has a dream, in which he is a butterfly. Whilst he is the butterfly, Zhuang Zhou has no awareness of his life as a man, and as a butterfly his life feels as real as it does when he is awake. The question the Zhuangzhi poses is this: does Zhuang Zhou dream he is the butterfly, or does the butterfly dream he is Zhuang Zhou?

Market panics have a similar, contradictory quality to a Daoist thought experiment. When they start, why they have kicked off is often a mystery, and they have a dream-like quality to them. But once they build up enough momentum, they take on a real, and rational, quality of their own. At the beginning, the panic seems made-up. Eventually, however, if you’re not panicking, you’re the one with the problem.

As pointed out in the following FT Unhedged post assessment of profitability and business model perception are key to understand whether a run may reach a self-fulfilling point, irrespective of whether the institution is well capitalized and complies with other regulatory requirements.

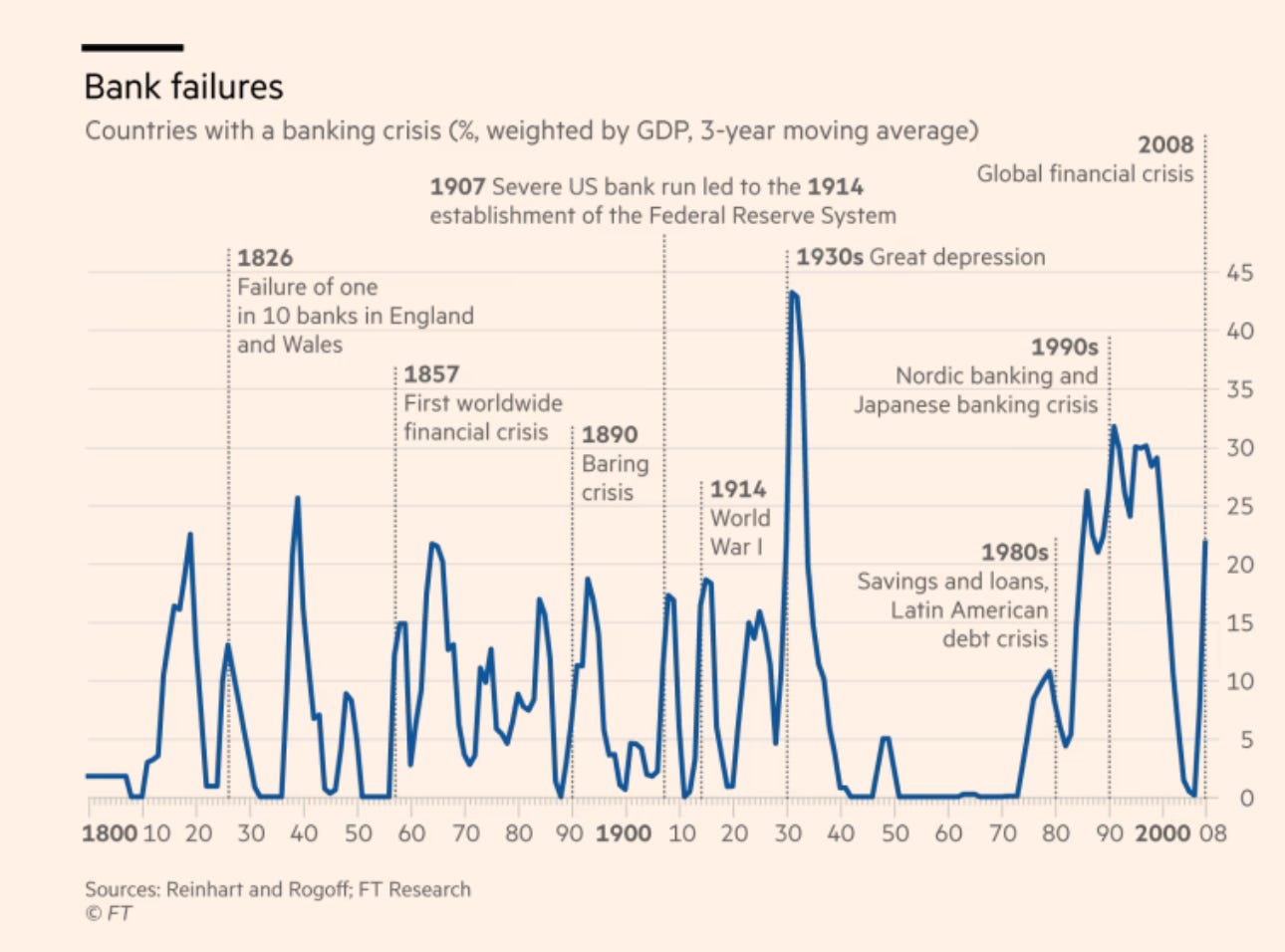

To finish the compilation, an interesting graph: